EARLY EXPLORERS

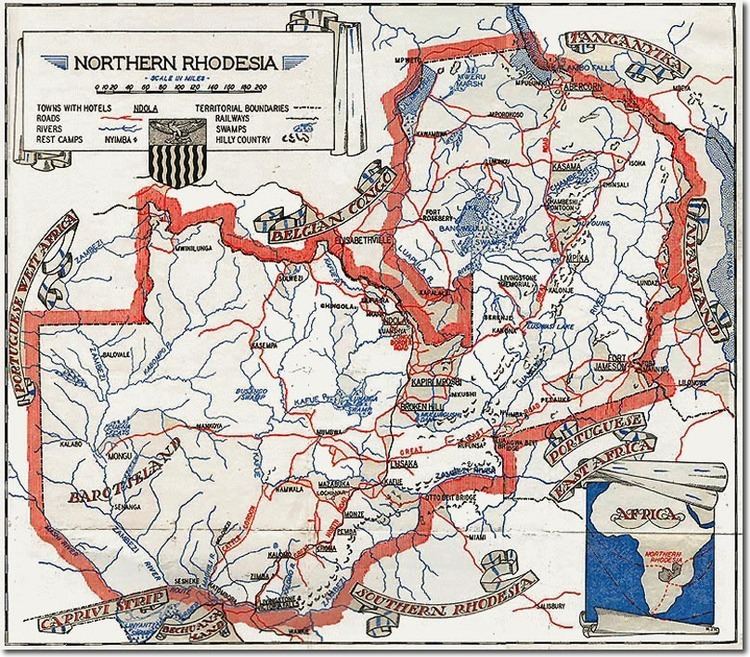

A BRIEF GUIDE TO NORTHERN RHODESIA

Information Department October, 1960 by Tm Wilson

The first recorded stranger to have penetrated far into the hitherto unknown territory of Northern Rhodesia was a Portuguese half-breed, Manoel Pereira, who started from Tete, a Portuguese settlement on the Zambezi, in 1796. There is little doubt that Portuguese interest in the hinterland at this juncture was heightened by the British occupation, in 17 95, of the cape of Good Hope.

Pereira crossed the Luangwa and Chambeshi Rivers and reached the court of Kazembe, a Lunda chief who had conquered large tracts of land in the vicinity of Lake Mweru. Two years later, 1798, the Portuguese Governor of Sena, Dr. de Lacerda, followed Pereira's route to the Kazembe country with a view tp opening up a trade route.

He died of fever before reaching Kazembe, and his chaplain, Father Francisco Pinto,took charge of the expedition. Pinto attempted to press deeper into Kazembe's country but was prevented by the Chief himself from crossing the Luapula, and had to return to Tete.

Portuguese contact with Kazembe was next made from the West Coast of Africa. Two half-caste traders - Pedro Baptista and Anastacia Jose - left Angola in 1802, and after visiting Kazembe valley went on to Tete, where they arrived in 1811. In 1832 Major Monteiro and Captain Gamitto undertook a further expedition to Kazembe's country but after this Portuguese interest seems to have declined.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kazembe

https://traditionalzambia.home.blog/white-tribe/portuguese/

British missionaries had already established themselves in Nyasaland, and in 1890 the British government's Colonial Office sent Harry Johnston to this area, where he proclaimed a protectorate, later named the British Central Africa Protectorate. The charter of BSAC contained only vague limits on the northern extent of the company's sphere of activities, and Rhodes sent emissaries Joseph Thomson and Alfred Sharpe to make treaties with chiefs in the area west of Nyasaland.

Rhodes also considered Barotseland as a suitable area for British South Africa Company operations and as a gateway to the copper deposits of Katanga. Lewanika, king of the Lozi people of Barotseland sought European protection because of internal unrest and the threat of Ndebele raids. With the help of François Coillard of the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society he drafted a petition seeking a British protectorate in 1889, but the Colonial Office took no immediate action on it.

However, Rhodes sent Frank Elliott Lochner to Barotseland to obtain a concession, and offered to pay the expenses of a protectorate there. Lochner told Lewanika that BSAC represented the British government, and on 27 June 1890 Lewanika consented to an exclusive mineral concession.

This (the Lochner Concession) gave the company mining rights over the whole area in which Lewanika was paramount ruler in exchange for an annual subsidy and the promise of British protection, a promise that Lochner had no authority to give. However, the BSAC advised the Foreign Office that the Lozi had accepted British protection. As a result, Barotseland was claimed to be within the British sphere of influence under the Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 1891, although its boundary with Angola was not fixed until 1905.

He sent Alfred Sharpe to obtain a treaty from its ruler, Msiri which would grant the concession and create a British protectorate over his kingdom. King Leopold II of Belgium was also interested in Katanga and Rhodes suffered one of his few setbacks when in April 1891 a Belgian expedition led by Paul Le Marinel obtained Msiri's agreement to Congo Free State personnel entering his territory, which they did in force in 1892. This treaty produced the anomaly of the Congo Pedicle.

LORD BUXTON IN NORTHERN RHODESIA: AN INDABA WITH YETTA III.

The illustrated London News, August 12, 1916

These interesting photographs illustrate " a very important meeting between Lord Buxton and King Yetta III. (late Litia E. Lewanika), at Kazangula, 50 miles above the Victoria Falls, on the Upper Zambesi." The reception, or indaba, took place on June 26. Lord and Lady Buxton and their party had just made a tour in Southern Rhodesia, and by June 20 had gone to Northern Rhodesia for a short holiday.

There is a scheme on foot for amalgamating Southern and Northern Rhodesia, but the High Commissioner made no definite pronouncement on the subject, saying that the Imperial Government would leave the decision to the colonists themselves. King Yetta III is the native ruler of Barotseland, or North Western Rhodesia. This and North-Eastern Rhodesia now form one territory known as Northern Rhodesia, separated from Southern Rhodesia by the Zambesi. It may be recalled that the late King of Barotseland,

Lewanika, died in February last. He came of a long line of Barotse rulers, and succeeded in 1877. In 1897 his kingdom was placed definately under British protection, the King receiving an annual subsidy from the Chartered Company. Lewanika, who was an intelligent and broad-minded man, visited England as a Royal guest at the Coronation of King Edward in 1902. In 1910 he went to welcome the Duke of Connaught at Livingstone, North Western Rhodesia. After the war broke out, Lewanika wrote to the administrator Northern Rhodesia: "The Indunas and myself we want to call in all our people, and then when they here we shall tell them to make ready for the war to help the Government.

We shall stand always to be under the English flag." King Yetta is following in the loyal footsteps of his predecessor. In the recent report of the British South African Company, issued in March, the Chief Native Commissioner says, with regard to the spendid loyalty of the natives of Rhodesia: "They view with calm confidence the termination of the war in favour of Great Britain and her allies. This is evident in that they continue to remain in a state of placid contentment unbroken by any unrest or dissatisfaction with the Government under which they live, and I have no hesitation in stating that, should occasion ever arise to call in their services for military purposes, they would loyally respond." During his tour in Rhodesia Lord Buxton visited Bulawayo, Livingstone and the Victoria Falls.

On June 21 the party motored to Katambovu, where they went into camp for a fishing expedition. It was at this camp that King Yetta was recieved by the High Commissioner. There were 2000 Barotse present on the occasion.

NDOLA INDABA

Circa 1873: The site at Chitambo, Lake Bangweulu, Zambia, where Scottish explorer Dr David Livingstone's heart lies buried. The portion of the tree carrying the inscription was cut down and is now deposited with the Royal Geographical Society in London. Livingstone (1813 - 1873), first visited Africa as a missionary where he visited fellow Scot Robert Moffat, and married his daughter.

He began exploring Africa with his wife, and later with his children too, becoming the first European to see sights such as Victoria Falls. He resigned from the Missionary Society but was appointed British consul for East Africa and led many expeditions to explore east and central Africa including a lengthy journey into the interior where he met a search party, looking for him, led by Morton Stanley. They became friends and travelled together before Livingstone's death in Zambia in 1873. His explorations revolutionized maps of Africa. He also campaigned for the abolition of slavery.

https://library.princeton.edu/visual_materials/maps/websites/africa/stanley/stanley.html

DAVID LIVINGSTONE

Zambia by Richard Hall

Supreme among these white travellers was David Livingstone, who first set foot on Zambia soil at the age of 38 and was to die on it nearly a generation later.

He pursued a myth derived from the writings of Herodotus, the Greek 'father of history', that the Nile had its source in a series of fountains. Livingstone's obsession that they bubbled out of the earth somewhere beyond Lake Bangweulu drew himto his death at Chitambo's village, 130 miles north-east of the Copperbelt. In his 10,000 miles of tramping, Livingstone crossed and recrossed Zambia, visiting places where probably no white man had been before; if they had, they had left no records....Continued...

Click on download file below....

Facts about Queen Elizabeth the 2nd visit to to Zambia for the Commonwealth conference on July 28 1979 :

- The Washington Post reported Zambia as a war torn country

- The colourful and care free welcome lacked tight security despite fears in Britain for her safety

- A spirited crowd of more than 5000 thronged the Lusaka Airport thunderous chants of Queenie Queenie could be heard from the locals whilst some citizen's of British origin could be seen openly shedding tears of joy.

- There had been pressure in Britain to cancel the visit and switch site of the conference.

- Fears of that she could be endangered by the presence of PF Guerrilla force's of Joshua Nkomo.

- Nkomo declined to accept an invitation from Kaunda to participate in social functions for the Queen, there was obvious a a sense of relief from the British Government.

-There was however a small crowd waving banners hostile to her Government's position on the regime change in neighbouring Zimbabwe Rhodesia.

-And on a lighter note the Queen came with her own Booze with twelve cases of tonic water and six cases of soda to go with it.

White Fathers missionaries in Northern Rhodesia.

The genesis of modern Zambia: 1890-1914

Missionary endeavour, the ambition of Cecil Rhodes and the technology of mining engineers combined to create the background of modern Zambia.

by Michael Langley | Published in

History Today

Volume 15 Issue 12 December 1965

WONDER HOW MANY PEOPLE REMEMBER that old white settler, “Chirupula”, Stephenson?

Over eight years have passed since the last of his many visitors called on him at Chiwefwe to listen, until dusk spread across the valley towards the distant Congo and the fearful Irumi Mountain, to the incredible stories of lais youth; of how he and the Bwana Mkubwa, John Fletcher Jones, had crossed the virtually unknown territory between Fort Jameson and the Hook of the Kufue; of how he had returned and founded the stations at Ndola and Mkushi, and of his life at Chiwefwe with his three African wives, as administrator, trader, recluse and oracle.

One of his favourite stories was of the mandate he gave the people of Chiwali in 1901—that there would be no more war, witchcraft or slavery. It was very passively received; in fact, he managed to maintain peace with disarming ease. Only much later did he discover the reason: among their three deities the Lala tribe had one who, according to legend, was fair skinned. So the stranger in their midst was obviously Luchere reincarnate, for only a god would dare to preach such an insane gospel.

Everything seemed, as Chirupula spoke, to be lost in the mist of tradition; yet this was a very real and significant event in an age when northwestern and north-eastern Rhodesia were developing administratively and economically at a rate that has not been equalled in the history of modern Africa outside the Transvaal.

Chirupula Stephenson who actually founded Mkushi and Ndola (11 kilometres from its present location) .

https://www.britishempire.co.uk/library/talesofzambia.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chiripula_Stephenson

http://www.spanglefish.com/Chirupula/index.asp?pageid=726930

MABLE SHAW (1889 -1973)

The town of Mbereshi was established in the year 1900 by the London Missionary Society, and was brought to fame in 1915 by Mable Shaw, that opened the first girls’ only school in Zambia. At the same time it opened a boys’ school and a hospital. Both the hospital and the girls’ school still exist today, and are run by The United Church of Zambia.

Mabel Shaw (1889-1973) was an English missionary and educator in Northern Rhodesia now Zambia. In her time "she was the most renowned missionary in Africa".

When she died in 1973, at the aged of 84, local people petitioned to have her remains brought and be buried at the mission grounds. It took the local people to organise for one of the headmen to travel to the United Kingdom with one mission of bringing Ms Shaw’s remains to Mbereshi, Luapula Province of Zambia.

Mabel Shaw’s ashes are buried at the chapel in Mbereshi. The epitaph at her burial ground reads: “This monument was erected to the glory of Christian friends and former students of Mable Shaw in loving memory.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mabel_Shaw_(missionary)

http://www.daily-mail.co.zm/mable-shaw-her-story-her-legacy/

https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/archives/24298c79-965e-3314-91fc-569ea792af6a

But why 1890 to 1914?

1890 was the year when Cecil Rhodes managed at last to consolidate his empire north of the Zambezi. In 1914, though the lights did not go out all over Africa, they were sufficiently dimmed by war and the subsequent economic depression to halt die initial impetus of development in Rhodesia. These twenty-four years were surely the most essential in Zambia’s progress into the modern world.

The dialectical historian of Africa might ascribe this progress simply to copper; another might say that it was due to the northward thrust of the railway; or to the swift advance of tropical medicine, combating the tsetse and mosquito; yet another to the establishment of sound adminstration founded on missionary endeavour.

The more discerning might ascribe it to the happy coincidence of all these factors, galvanised by the energy of Rhodes, that “brooding spirit”, as Kipling called him; for northern Rhodesia fell astride die highway of his dream. Let us look at Rhodes’s incursion north of die Zambezi and then briefly at some of these main forces, and, where possible, interrelate them......Continued

Please Read by downloading...

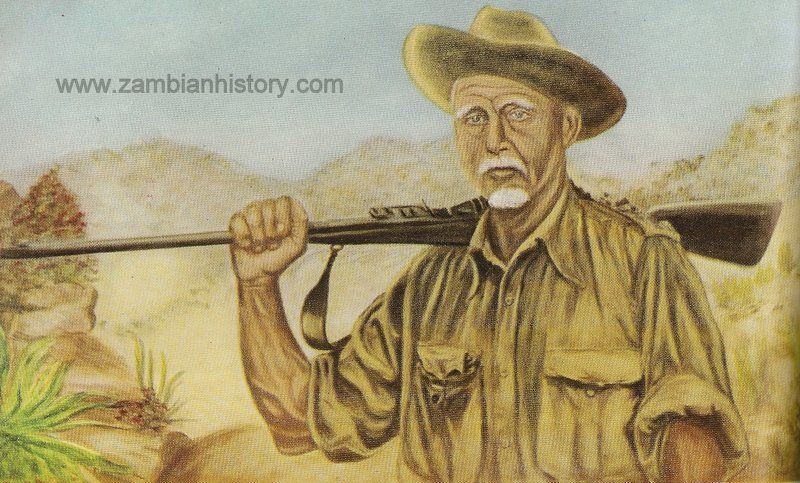

Fredrick Courtney Selous

Hunter, Explorer, Rhodesian Pioneer.....

The Rhodesian and Central African Annual 1954

The above painting of Fredrick Courtney Selous, D.S.O. was done by Mrs. Joan Jocelyn. The painting was done from an autographed photograph of Selous which was taken by Captain Cherry Kearton, a fellow officer of the Royal Fusiliers. This photograph is now the property of McMillan Memorial Library in Nairobi.

Selous was once asked how his name was pronounced. He replied: "You may call me 'See-loo' or 'Sel-oo', but for goodness sake don't call me 'Selouse'!"

From 1871 for a decade Selous hunted and traded ivory before he joined the British South Africa Company. He did much to make the way of the Pioneer Column of 1890 as smooth as it was. He chose the road and plotted the course and it was he who named the steep approach to Fort Victoria providence Pass.

His first shooting was done as a member of the cadet corps at Rugby. During a year's sojourn in Switzerland he stalked and bagged two chamois. He kept in a glass case a marten trapped by him in Switzerland and possessed a fine collection of butterflies and bird's eggs.

Selous, to whom danger and adventure were the very essence of life, had his share of them. He carried on his right cheek a deep scar. It is said that while hunting elephant an African servant loaded one of the four-bore guns with a double charge. On discharging the gun Selous is said to have been hurdled backwards unconscious as the stock of the weapon was shattered.

Thus was caused a wound the scar of which remained with him through life. He and his wife rode on horseback from Essexvale to Bulawayo when the Matabele plundered their home, the only thing they saved being their wire-haired terrier, Trot. One of his treasured possessions was the skin of a lion riddled with holes made by Matabele assegais. The skin was presented to him by Lobengula.

In the first world war, as a member of the 25th City of London (Royal Fusiliers) Legion of Frontiersmen he served in German East Africa. There he displayed the fearlessness which was characteristic of him, and, at the age of 65, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. Two yeard later, in 1917, leading an attack near Kissaki, he was wounded. He continued to lead, but was hit again and fell dead.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Diaries of Alexander Collie Anderson

Mwenga River Camp & Mumbwa, Zambia

1902-1908

http://www.seddepseq.co.uk/Anderson/Diary_1902.htm

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A COLONIAL SURVEYOR AT WORK

The field diary of W. G. Fairweather, Assistant Surveyor, Northern Rhodesia Government, 1913-1914

The diary consists of seventy-two pages of typescript and it spans a period of eight months from 5 September 1913 to 11 April 1914. During this period the author was continuously on tour and he covered some 600 miles on foot, surveyed seventeen farms totalling some 30,000 acres and also did topographic mapping in country which was previously unsurveyed. In Fairweather's own words, what he compiled daily throughout the tour was “a diary not a treatise on topographic surveying” and indeed what makes the document unusual is that it is a personal record meticulously maintained for the author's personal satisfaction and not an official tour report. It includes frequent mention of his day to day work, certainly sufficient to enable the reader who has any knowledge of survey practices to appreciate what he sought to achieve and the sort of logistical and practical problems which he encountered in the course of carrying out his professional duties. Nevertheless, it is at least as interesting as a record of the impressions, beliefs and attitudes of an expatriate European colonial civil servant during an abnormally long, eventful and at times arduous journey. In 1951, the year before his death, Fairweather was living near Livingstone which is presumably why his diary was deposited in the Livingstone Museum.

In 1916, Fairweather was appointed Acting Chief Surveyor, whilst his superior was on leave. The following year, he was promoted to Chief Assistant Surveyor and Examiner of Diagrams, and on the retirement of his predecessor in 1920, he was appointed Chief Surveyor, an office which he held until his retirement in 1939. He was awarded OBE in 1932.

THE YEAR 1933 IN NORTHERN RHODESIA

W. G. Fairweather, O.B.E., B.Sc., Director of Surveys

The general depression in world trade has affected the country to no small extent during the year in almost all branches of departmental activity. It has been particularly reflected in the Survey Department by a reduction in applications for land from new settlers, and in sub divisional surveys· carried out for private landholders. In all other branches, however, the Department has had more on its hands than its now limited staff could cope with, and there is the danger of work getting behindhand and being put aside for a future occasion whilst new projects are dealt with to supply immediate requirements. Any sudden revival of prosperity, such as happened some years ago when the Mining Companies commenced their prospecting, developing and construction work on what was then an unprecedented scale for this Territory, will most assuredly find this Department ill-equipped to cope with the demands which will inevitably fall upon t from all sides, though no doubt the Staff will respond to the demand in the same manner as on previous occasions, having now become more or less inured to working under conditions of severe strain and

financial stress.

To continue reading click on the link....

Short stories...

Robin Clay: My father was DC, Isoka during WW2. As part of his duties he would go out "on tour", a.k.a. "Ulendo", visiting the villages and talking to the headmen / indunas / chiefs, about their problems, take the Census, collect tax, try minor cases, explain Government Policies, etc., etc., etc.

This is a map showing his tours of 1940 - each would take 3 or 4 weeks.

He had a team of porters to carry his "office", camping gear, food, etc.. He would go on ahead, usually by foot, but sometimes by bicycle or horseback; he would "do his business", while they set up camp, fetched water, dug a latrine, etc, etc..

In the afternoon he would go out to "shoot for the pot" for them all - and maybe for the village too.

Sometimes my mother would go along, and for many villagers she would be the first white woman they had ever seen.

And sometimes we children would go too, carried in a machila by porters - one of my earliest memories !

http://www.spanglefish.com/GervasClay/index.asp?pageid=517694aXM

To Independence and Beyond: Memoirs of a Colonial Commonwealth Civil Servant

by Peter Snelson

Peter Snelson's career covered the latter years of colonial rule in Northern Rhodesia (1954-64), the early years of Zambian Independence (1964-68) and then almost 20 years as a senior official in the Commonwealth Secretariat.

After reading History at Cambridge and a short-service Commission in the R.A.F., he went out to Northern Rhodesia in 1954 as an Education Officer in the African Education Department. A short spell at Munali, N.R.'s premier secondary school, was followed by a longer spell as an Education Officer in Eastern Province.

He then went to Northern Province firstly as the Education Officer in Chinsali District and then as Provincial Education Officer. The Province was widely affected by violence and intimidation during the Nationalist campaigns for an end to the Central African Federation and early independence. Many government buildings and facilities were destroyed during these campaigns including a large number of school buildings.

The Province was also the home of Alice Lenshina's Lumpa Church, whose suppression in 1964 was attended by bloodshed on a horrendous scale. The author's account of these events and his reflections on them will be read with much interest by old N.R. hands.

In 1964 he was appointed P.E.O. of the Copperbelt. This was a particularly difficult post, as the Province contained a considerable number of European schools which had our congratulations and grateful thanks to the Chairman in particular and of course to you yourself. Sir, for all that you and your colleagues have done in recent years.

previously been administered by the Federal Ministry of Education and were now to become multi-racial under the Zambian Ministry of Education. With racial prejudices strongly ingrained on the Copperbelt, the largely trouble-free introduction of multi-racial schooling is a heartening story.

His final appointment in Zambia was as Director of Planning in the Ministry of Education in Lusaka. Here he was to witness the debate between the African politicians pressing for a vast and immediate expansion of educational facilities and a largely expatriate group of advisers advocating a more Fabian approach.

At the Commonwealth Secretariat he was mainly concerned with educational matters and particularly with the setting-up and operation of the Fellowships Training Programme of the Commonwealth Fund for Technical Co-operation. He was also required to undertake several special assignments. These included the servicing of the V.I.P. Commonwealth Observers Group, which monitored Zimbabwe's pre-independence elections, and representing the Secretary-General of the Commonwealth at the Independence celebrations at Tuvalu in the Pacific.

During his career as a Commonwealth Civil Servant he visited nearly all of the 50 odd member countries. His postscript includes an interesting review of developments in the former colonial territories since independence.

Although the author has been a civil servant throughout his career, he is far from being an establishment figure and some of the views he expresses may not find favour with all his former colleagues.

The provision of chapter notes and thorough indexing will be very useful to those wishing to study the late colonial/early independence period N.R./Zambia.

His engaging style of writing, the inclusion of extracts from his diary, snippets of family views and the odd dig at the good and the great, combine to make it a most readable book. It should do something to weaken the stereotype image of overseas civil servants as projected by so much of the media.

Remnants of Empire. Memory and Northern Rhodesia's White Diaspora

by Pamela Shurmer-Smith

Unlike Zimbabwe (Southern Rhodesia) and South Africa, Zambia (Northern Rhodesia) lacked its Doris Lessing and Nadine Gordimer to provide an image of its colonial society. Pamela Shurmer-Smith's collection of oral evidence from the relatively small number of white people who settled there prior to independence in 1964 will thus fill a gap, and appears just in time to capture the very varied testimonies of the 'white Diaspora'. Her book is particularly valuable for putting to rest the common stereotype of the white settler sitting on his veranda enjoying his sundowner while his labourers toil in the fields. Her informants varied tremendously in background, from the Afrikaner miner who brought his racist ideas to the Copperbelt to the paternalistic civil servants sent out by the Colonial Office, and those who fled the austerity of post-war Britain to find a new life in the sun.

'Remnants of Empire' reviews these experiences, moving through the rapid changes of the late 50s that completely transformed what had been a very quiet and seemingly permanent political system. The year 1964 saw the independence of Zambia in what in retrospect was a fairly peaceful transition, in contrast to what happened elsewhere in southern Africa in the 1970s onwards. The diaspora, the emigration of whites from Northern Rhodesia, was similarly a smooth process. The later chapters of her book discuss the experiences of the Diaspora in some detail, ranging from the anger of those who felt betrayed by British policy to those who left bidding Zambia all the best, but leaving with a slight twinge. Indeed, it is surprising how many renewed their acquaintance with Africa later.

As a historian I was particularly interested in her initial chapter about memory: what we remember, what we don't want to remember, what we should remember, and what we choose to forget. It is all too human to distance ourselves from views we had in the past which are no longer acceptable. Colonial rule and the race prejudice that unfortunately flourished under its wings was one such.

A valuable historical record of a relatively unknown former colonial territory.

Additional Review by Mark Henwick The story of Northern Rhodesia becoming Zambia is like a patchwork quilt, and that is exactly how this book portrays it, relying on the words and phrases of the people who lived it to tell the tale. It is the only way such a diverse experience could be given a balanced exposition.

My father was District Commissioner at Broken Hill (now Kabwe) at the time of independence. He stayed until the end of 1969, working initially in the Zambian government's 'Youth Development' ministry. I was born in Kasempa Mission Hospital, and at school in Broken Hill's Parker Primary and then Lusaka Boys School before being sent south to Springvale in Southern Rhodesia. When I moved to the UK, I went to a school where the bursar was another DC from Northern Rhodesia. With that background, of course many of the names and almost all of the stories are familiar to me.

We were in no way refugees, and I have been lucky all my life, but I find my memory of the shock of being uprooted from Africa and replanted in the UK is echoed and re-echoed in these stories.

It was never one of the glamorous countries of Africa, but NR/Z put a marker in all our souls - witness the associations that still meet all over the world.

Anyone who was there, or anyone who has the slightest interest in a balanced view of this part of history should read this book.

Additional Review by D. Grewar The story of the diaspora of Northern Rhodesians is a difficult subject to record in a fair and balanced manner because of the many diverse views of Northern Rhodesians. I think Pamela Shurmer-Smith done an excellent job in weaving together the personal stories of so many people with an unbiased view of the history of our country.

I thought that maybe I was alone in being unable to settle back in England the land of my birth after 21 years in Africa, but I find that the majority of returnees had the same difficulty and many of them have moved on. They either returned to Africa or went to other parts of the world or some even became eternal ‘men in a suitcase’ moving like gypsies from one location to another.

This book brings alive the trauma of having to uproot oneself from one’s long time friends and neighbours when or shortly after Northern Rhodesia became Zambia in 1964. The cruelty was compounded by the restrictions on taking one’s honest and hard earned life savings with one. This was made even worse when currency restrictions were expanded to include personal and household effects. Yes, there were reasons for it but for the average Northern Rhodesian who had no option but to leave; for him to have to leave his own life savings behind was just pure theft on the part of the new regime.

The expatriates who came to Zambia after Independence are a different story from NR’s. They knew they were just hired on a short contract basis and had no illusions about the country becoming their home. Even so many if them feel a strange nostalgia for their years in Zambia that is only too evident in the social media pages.

The residents of Northern Rhodesia were roughly divided into the Government or PA types and the rest. The PA community (the British Colonial Civil Servants) were deliberately transferred from station to station and given 6 months home leave every 3 years to prevent them forming any attachment to their host countries. Despite this many did form strong attachments to Northern Rhodesia (especially those who served in the Northern Rhodesia Police).

The non-PA community was divided into the commercial / trading, the mining and the farming communities. Most of the miners came from South Africa and SR and would work a few years on the mines before returning to their farms down south. After a few bad seasons on the farms they would return to the Copperbelt to save up another grubstake. They had little interest in NR or its peoples and were only there to make money. In a way one could call these temporary sojourners the forerunners of the ‘expatriates’ who came after independence. Even so many of them did form an attachment for the affluent and relaxed Copperbelt lifestyle.

Among the non-PA group and mainly in the trading and farming communities were the ‘settlers’, the real Northern Rhodesians, who actually thought that they were going to live in NRZ for ever and who were prepared to adapt to changing conditions and live under an African dominated government. I identify myself with this group. I think these settlers or at least the ones who had to leave NRZ were the ones who felt the loss most poignantly because they lost not only a comfortable lifestyle and their properties and assets and in some cases their families, but most importantly they lost their dreams. They suffered something like what the Yanks call post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in their troops returning from battle fronts. Time eases the pain but many of us will take the mental scars with us to our graves.

The emigrants had a wide variety of success in their new lives after leaving NRZ from Neville Isdell who became head of the giant Coca-Cola organization to the chap who ended up penniless sleeping in a New Zealand garden shed. Most however returned to the western humdrum life of wage slavery as university bursars, teachers, policemen or lawyers with only their memories of a life in the sun to brighten their dull lives.

The book is generally sad and nostalgic but I found the saddest story was that of Heather Hunt who was born in Broken Hill hospital in 1939. She married Des and they built up a farm near Broken Hill from scratch, even making the bricks themselves. After Des’ death Heather stayed on until July 2014 when she moved to the UK at 75 years old. She had no children left in Zambia to take over the farm and look after her in her old age so she had to sell the farm. I really feel for Heather. I hope she finds some happiness in the years that remain for her. What a crying shame after sticking it out through thick and thin in Northern Rhodesia and Zambia that she has had to leave.

District Officer in Tanganyika: 1956 - 1960 Part 2: The Memoirs of Dick Eberlie

by Dick Eberlie

From the Cam to the Zambezi: Colonial Service and the Path to the New Zambia

by Tony Schur

From Northern Rhodesia to Zambia: Recollections of a DO/DC 1962-73

by Mick Bond

I am always struck when I read of the men who went to Africa as administrators how, living and working in a strange land, they met the unexpected with such steady nerves. This applies no less to those who went out at the end of the span of seventy or so years of British administration than it did at the beginning.

In

Dick Eberlie's charming book (District Officer in Tanganyika) he describes how, whilst on a particularly wet and uncomfortable working safari early in his first posting in Tanganyika, he became aware that he had become blind in one eye. Although greatly distressed, he completed his safari and when he got back to the boma, he played a game of squash and buried himself in his work. No headless chicken he.

In Northern Rhodesia/Zambia, one of the first duties of the District Assistant, Jonathan Leach, was to warn the Senior Prison Warder that a certain prisoner was to be brought to the boma early the following morning for transportation to Provincial Headquarters. In the dusk he walked through the mango-tree grove to the gaol to pass on the message. "Warder!" I called in my best military/colonial voice. Not a sound.

Met with an eerie silence his now perhaps less military voice rose in crescendo until a ghostlike figure emerged in the evening gloom. The apparition timidly explained that he was the senior prisoner. He had the keys on his person whilst the warders had gone visiting. With the aplomb of a veteran Leach transmitted the District Commissioner's orders to the senior prisoner, who proved worthy of his high office, and the dangerous felon appeared at the boma the next morning, manacled, escorted and on time. (From the Cam to the Zambezi.)

On a more sombre note, Mick Bond (From Northern Rhodesia to Zambia) recounts how he and his colleagues were faced with the completely unfamiliar religious Lenshina movement, or Lumpa, that had boiled up in north-eastern Zambia in 1964/65. As with similar agitations in Africa, it involved many unnecessary deaths and tore villages and clans apart. While the new Government exacerbated the tragedy with politics (again, a novel situation for DOs and their superiors) the administrative officers worked tirelessly to carry out the orders they were given to move the Lumpa people back to their original villages, while ensuring that they acted with humanity. Dr Kenneth Kaunda, the then Prime Minister, must not be forgotten when, at the eleventh hour after listening to the hotheads in his fledgling Government, he ruled that the Lumpas were to be forgiven and accepted back into their villages...

The security and administrative officers sighed with relief. (From Northern Rhodesia to Zambia.)

The wives also met the unexpected with courage and resourcefulness and made their contribution. Their duties and interests were many and varied. They welcomed endless visitors; they helped with the local women's self-help or craft groups; they kept up the spirits of the bachelors far from home by teaching them the rumba or they went on safari with their husbands to help collate the electoral lists. I am glad that Tony Schur, who edited the collection of accounts in From the Cam to the Zambezi, did not forget the women and included accounts from three of these invincible volunteer members of the administration.

Two of the books under review cover Zambian pre-internal self-government and the transition to independence. The third is about Tanganyika just before independence. It is interesting to detect the difference in atmosphere between those two countries. Although it is difficult to put a finger on it, it seemed to me that throughout the Zambian accounts there runs a certain uneasiness. This is surely partly caused by the high tension of the Unilateral Declaration of Independence in Southern Rhodesia, war in Angola and turmoil in the Congo bringing waves of refugees. These crises across the borders probably also exacerbated the tribal and party strains that were building up during Zambian Internal Self-Government. The new DOs and cadets in Zambia appear to have been under greater pressure than many of their colleagues in Tanganyika; working in what appeared to be an atmosphere of disquiet.

In Tanganyika

Dick Eberlie records that the population's concerns were more often with roads, cattle and marauding hippo wrecking their shambas but he also comments that "arranging [local] elections was worthwhile and sometimes amusing work" That does not sound too tense. The UN Secretary General, Dag Hammarskjold, who visited Tanganyika in January 1960 was impressed by the contrast with Ruanda Urundi where he had found violence and revolution in the air. Yes, the Tanganyika administrative officers had the usual time-consuming workload checking on the village markets and schools, getting medicines to the dispensaries, dealing with the destitute, building bridges, arranging voter registrations or struggling with the legal complexities involved in such crimes as the alleged theft of a duck by a small boy - and worse too, of course. Despite their many duties, there appeared to be more opportunity in Tanganyika to play tennis, to party, to fish in the hills, or racing sailing dinghies off Dar es Salaam of an evening.

What happened next?

Dick Eberlie leaves us wondering. His story ends when he flies back to England to enjoy his end of tour leave in 1960. But I have learned that he is busy writing two further books, one about his later service in Tanganyika and the other about his subsequent assignment in Aden as Private Secretary to the governing High Commissioner Sir Richard Turnbull.

Because the other two books dip into the early years of independence we have an idea what happened to some of the British officers who served Zambia in the years of transition and even later, but it is distressing to read Valentine Musakanya's story (From the Cam to the Zambezi). It began with such hopefulness following his parents' great sacrifice to ensure that Valentine was well-educated. He was much liked by his fellow cadets who attended the Overseas Course in Cambridge and he joined the civil service in Northern Rhodesia which included working as a District Officer. At Internal Self-Government he was asked to help establish the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

In the 1980s there followed a period when he was shamefully treated. Arrested, tortured and sentenced to death, he was eventually acquitted in 1985 but his health was broken and he died at 62. How did he keep his head when all about them were losing theirs? He wrote "I have found out that although I love Zambia so much, I perhaps love a truthful approach more, because only the latter will make her truly free." I hope Zambia will not forget him and will honour him and that sentiment.

Zambia: The First 50 Years (International Library of African Studies)

by Andrew Sardanis

Andrew Sardanis, a Greek Cypriot born in 1930 and holding strong anticolonialist views, migrated to Northern Rhodesia in 1950. For the next seven years he worked mainly in the North West Province buying produce from the villagers and finally settled in Chingola on the Copperbelt in 1957. There he came into contact with African politicians and civil servants and became involved with Kenneth Kaunda's United National Independence Party.

He stood as a candidate for UNIP in the 1962 election which produced the first African dominated government. After independence he was appointed Chairman of the Industrial Development Corporation and subsequently Permanent Secretary, first of the Ministry of Commerce and later of the Ministry of Finance. He left Government in 1971 and became involved in a multinational business group whose interests extended to thirtyone African countries. He still lives in Zambia and has maintained close contact with Zambian politicians over the years.

Zambia: The First Fifty Years is the third in a series of books by Sardanis.

Africa: Another side of the Coin is described as "a memoir that covers the expiring years of Northern Rhodesia and the birth and travails of Zambia in the early years of independence".

A Venture in Africa describes Sardanis's business career. The new volume sets out to be "a detailed examination of most major events in our history since independence". Sardanis was unhappy at the creation of the one party state and refers to his advice to Kaunda on this and other topics as being generally disregarded. He deals with the return to democratic government with the election of 1991 and reviews the Presidencies of Chiluba, Mwanawasa, Rupia Banda and Sata.

There is an element of autobiography to the book but essentially it is intended to be a history of the first half-century of Zambia's existence. Sardanis does not claim to be a historian. The non-judgmental approach of modern colonial historians such as Paxman, Tristram Hunt and Kwarteng is not for him. He has strong views on every issue and expresses them forcefully. Very few escape his criticisms - and certainly none of Zambia's presidents. Perhaps unsurprisingly Kaunda receives the most praise. Criticisms of him are made somewhat reluctantly although Sardanis makes it plain that he would have been a far better president and Zambia a far happier country if he had listened more carefully to and acted on Sardanis's advice.

Overseas advisers brought in to assist the Zambian government are described as unrealistic and he is scathing about all those involved in the civil proceedings against ex-president Chiluba in London and about the British High Commissioner in Zambia. In particular however he is critical of the pre- Independence government. His strong anti-colonialist views are more forcefully expressed in Africa: Another Side of the Coin than in the present book but even here he refers to the total lack of development before independence in contrast to the money spent in particular on education post- 1964. His views on expatriate civil servants are given in a throwaway remark on the Barotse issue - "the provincial administration of Northern Rhodesia being out of touch as usual".

The pre-independence roles of some Europeans are perhaps viewed more generously by other present day Zambians. Hugh Bown has written a report of the visit of a group of expatriates last autumn to the fiftieth anniversary of independence celebrations. He comments that the Association of Freedom Fighters came to him with a proposal to raise a monument to the European Freedom fighters. He ends "Meeting with so many people who viewed the road to Independence as a struggle and even as a fight must prompt thoughts on the virtues or shortcomings of the government which ruled for forty years from 1924. However Peter Kasanda who did so much to organise this trip for us has written to say that our visit was appreciated. Shakespeare may have said that the evil which men do lives after them but in this case it seems that by and large it is the good that is being remembered and built upon."

Sardanis also comments in some detail on other writers on Zambia with whose views he does not agree. Hugh Macmillan's book

An African Trading Empire: The Story of Susman Brothers and Wulfsohn comes in for particularly rough treatment as does his contribution to

One Zambia, Many Histories. The four Zambian contributors to this get a nod of approval but the eight "foreigners, like Macmillan, stretch facts to suit their arguments to prove their predetermined conclusions".

It could be argued that this comment would not be inappropriate for parts of this book. It is likely that any reader with an interest in Zambia is going to be irritated by it at some stage. It is nevertheless a fascinating read. There is a wealth of interesting information and while his criticisms are unrestrained and plainly biased they do give considerable scope for thought.

FEDERAL CLOTHES COLOURSCOPE

The Rhodesian (Central African) Annual, 1962

The fashion colourscope takes on new meaning in Central Africa, where fabrics, colours and clothes are designed to enhance the beauty of women of many races. Here is the designer's paradice, awhirl with the excitement of emergent African womanhood eager to submit to the spell of fashion, fervent new followers of the dictates of Europe's salons.

‘Moral evil, economic good’: Whitewashing the sins of colonialism

How war, violence and extractivism defined the legacy of the empire in Africa, and why recent attempts to explore the ‘ethical’ contributions of colonialism risk rewriting history and undermining progress.

- Sabelo J Ndlovu-Gatsheni

- Historian, professor and decolonial theorist.

https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/2/26/colonialism-in-africa-empire-was-not-ethical